Creating a new item as a child of '/blog/oop-orchestra'.

Object-oriented programming is like an orchestra

Maddy Guthridge — July 3rd, 2025

What is the first thing you think of when you think of object-oriented programming? For most, the key features are classes, inheritance and polymorphism. However, when you ask “object-oriented nerds” (said with love), such as “Father of OOP” Alan Kay, they will often say that the core principle is instead message passing. In this blog post, I’ll throw my hat into the ring in agreement.

When designing object-oriented systems, huge amounts of consideration are given to the design and maintainability of the code-base, perhaps more-so than in any other programming paradigm. This design obsession manifests itself both through excellent resources such as Alexander Shvets’ refactoring.guru, as well as in incredible parody of the often-over-designed nature of object-oriented code-bases.

This term, I’ve been tutoring UNSW’s COMP2511 “Object-Oriented Design and Programming” course, which has given me the opportunity to delve into the object-oriented approach to software design in search of ever-improving explanations to give to my students. Today, I think I created an example good enough to share with the world.

The musician

Imagine you are a talented musician, perhaps Elton John or Dolly Parton (wouldn’t that be lovely!). Musicians are incredible – they use their mastery of their instrument to convey not just rhythm and melody, but emotion and metaphor. However, this takes an enormous level of dexterity and skill, meaning that there is an upper limit to the “complexity” of a piece that can be created by a single musician. When the most-talented organist plays 3 staves simultaneously, or even when Joe “hits it” on his photoplayer, musicians often cannot produce the full range of musical expression by themselves.

The ensemble

Fortunately, musicians almost never work alone. Creating many forms of music requires intense coordination between many people. When you watch any good ensemble perform, you’ll see huge amounts of communication between musicians. Whether it’s the nod of the bassist to the drummer when they improvise a perfectly-timed fill together, or the glance of the saxophonist wondering when her solo will end, musicians are constantly communicating musical instruction and information with each other through an often-informal, but widely-understood system of non-verbal cues. This is perhaps best exemplified through the directions of a conductor.

The conductor

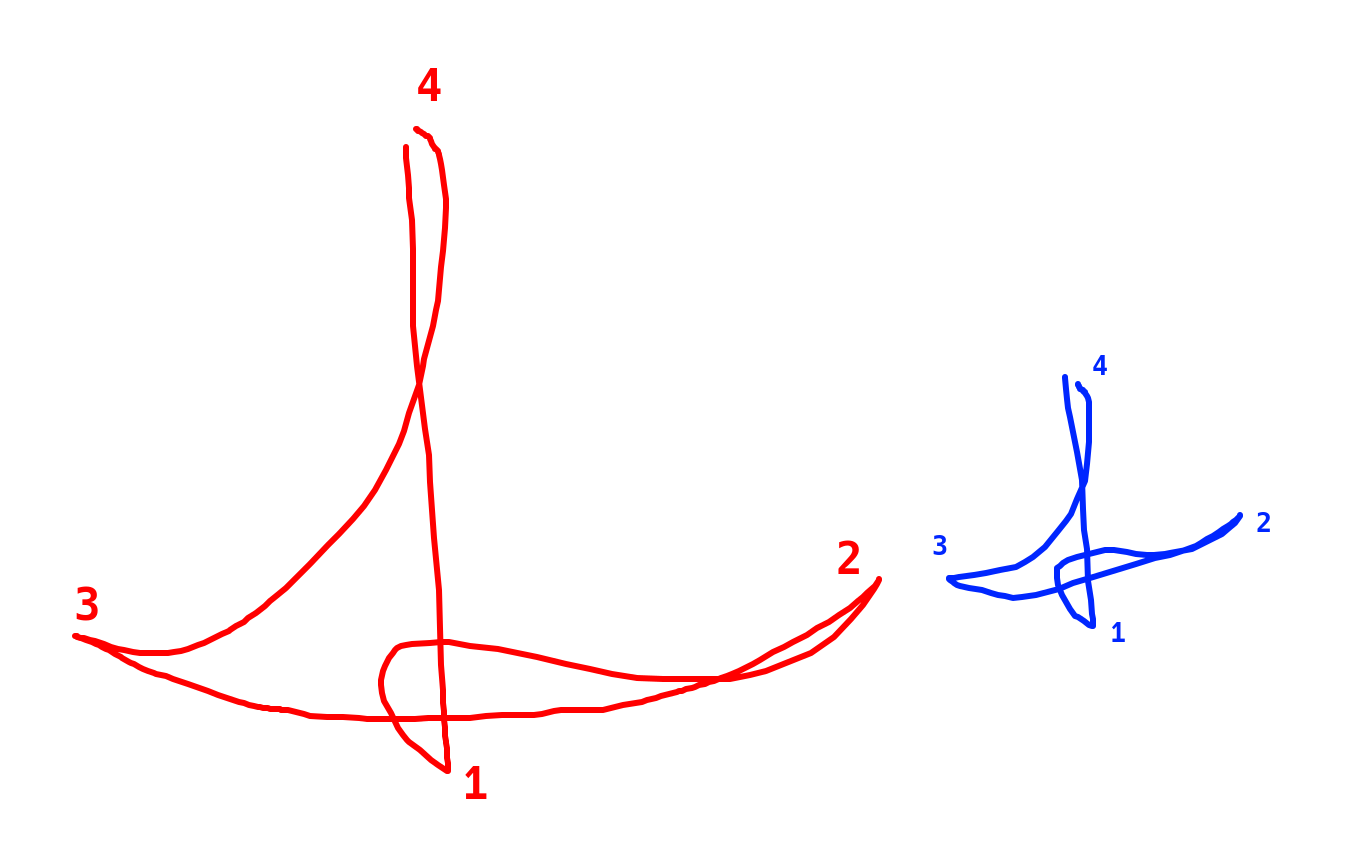

In an orchestra, the role of a conductor is to direct and synchronise a large ensemble such that the musicians (hopefully) produce a coordinated and beautiful piece of music. This is done through the movement of a baton (as well as the use of other hand gestures) to indicate meter, tempo and style. In my small amount of experience conducting (the Sesame Street theme played by the Manning Valley Youth Concert Band), I learnt that the messages conductors convey to players are both simple and clear. Consider dynamics (loud vs soft music), and guess which dynamic is indicated by each movement below.

Of course, the answer is that the left option is louder. Just by changing to a larger hand movement, I can indicate an increased volume. These simple gestures are used to convey all kinds of musical instructions, from articulation and tempo adjustments to cuing soloists.

Message passing

Importantly, the conductor of an orchestra does not tell musicians how specifically to play their instrument, or even what to play (each musician has their own part-score with their own part of the music). The messages are generic and can be understood by any musician regardless of their instrument. A cellist doesn’t need to be told to use greater bow pressure and speed, they are simply instructed to play louder. A flautist need not be told to use a “tongue attack”, the conductor simply indicates that they want the music to be accentuated. In essence, each musician can be trusted to be responsible for their own sound, and is able to create the desired musical interpretation by receiving generic directions, where those directions can be understood by any other musician. The benefit of this is obvious to any musician: the generic message-passing nature of a conductor means that tens or even hundreds of musicians can play in concert (pun intended). As object-oriented designers, we would say that musicians encapsulate their musical abilities.

Encapsulation

This idea of generic message passing between multiple entities, when done correctly, leads to all components of a system being encapsulated, meaning they are responsible for their own functionality. The conductor need not know how to use a staccato articulation on every instrument – they simply need to use short, sharp hand movements, and the musicians will handle the rest. This is the ultimate goal for any designer of object-oriented systems: the ability control complex systems through simple messages, with any complex underlying techniques being abstracted away, and as such, my advice to any programmer new to OOP is to consider their software to be like an orchestra. It is easiest to write, control and maintain software if all the parts of it are responsible for themselves, but communicate with each other through clearly-defined and generic message-passing.

An example: representing musicians in code

This point may be more clear given some proper code examples, and so consider this snippet of Java code:

class Cellist {

private double bowPressure;

private double bowSpeed;

public void setBowPressure(

double newPressure);

public void setBowSpeed(

double newSpeed);

public void bowStart();

public void bowStop();

// And so on...

}

Let’s see how our conductor could direct a cellist to play some music

class Conductor {

public void example() {

// My wonderful cello teacher

var cheryl = new Cellist();

// Let's make her play fortissimo!

cheryl.setBowPressure(0.95);

cheryl.setBowSpeed(0.8);

// This gets even more complex when

// you consider that different bow

// speeds and pressures are required

// for different pitches of note!

// Oh dear!

cheryl.bowStart();

Thread.sleep(1);

cheryl.bowStop();

}

}

The system for doing so is far from ideal. In order to direct Cheryl’s performance, our Conductor must instruct her using cello-specific methods, making it far harder to work with her as a part of an ensemble. Let’s improve this by refactoring our Cellist‘s interface to reflect how our Conductor would actually interact with them.

class Cellist implements Musician {

// Internally, cellists still use the

// same data

private double bowPressure;

private double bowSpeed;

// But their public interface is far

// nicer.

// In particular, it matches that of

// the interface `Musician`, meaning

// that our conductor can direct them

// in the same way as they can for

// everyone else.

@Override

public void setDynamic(Dynamic newDynamic);

@Override

public void setArticulation(

Articulation newArticulation);

@Override

public void play(float duration);

}

Look how the conductor’s interactions became so much simpler!

class Conductor {

public void example() {

var cheryl = new Cellist();

cheryl.setDynamic(0.95);

cheryl.setArticulation(

Articulation.Staccato);

cheryl.play(1);

}

}

With our new interface, a conductor could direct the playing of hundreds of musicians without ever worrying about the specifics of how those musicians play their specific instrument: an ideal abstraction. In particular, the improved design:

- Avoids getters and setters for internal details.

- Uses a standard interface to handle messages in a manner consistent with other musicians.

- Has its interface designed to maximise the simplicity and utility of interacting with it, rather than prioritising the simplicity of the internal code.

In summary

Object-oriented programming is an excellent paradigm for designing complex systems, but in order to create the most-maintainable code, a designer must focus primarily on generic message passing, such that components of their system can interact in idiomatic and simple ways, even if the underlying effects of these interactions are complex. While inheritance, interfaces and other common OOP features are helpful for achieving these goals, they are useless if software using them does not use them to optimise the design of the code’s message passing. Through thoughtful design of message passing, our code becomes encapsulated, generic and maximally maintainable.

Thanks for reading!

Maddy